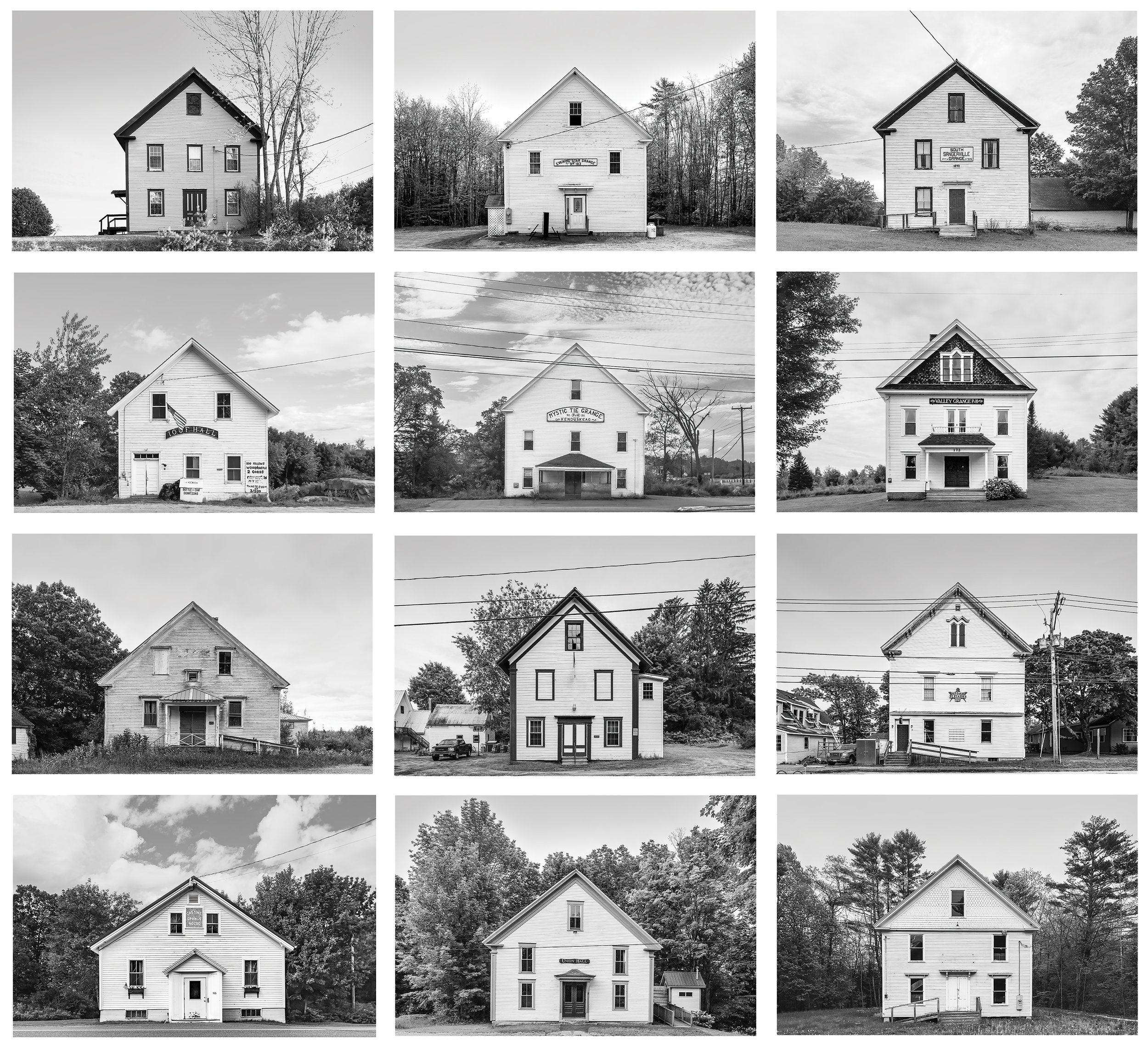

Meeting Hall Maine

Our human desire to come together is expressed in the architectural typologies of Maine’s historic meeting halls. My photographs of these vernacular structures act as portraits. I aim to tell an American story of resiliency, obsolescence and adaptation by reflecting the current state of this once thriving network of translocal movements that were built and maintained collaboratively by local people for generations. As memberships in volunteer societies die out, halls across the state are at risk for being razed or lost for civic use. These community created forums are vital for invigorating American democracy by providing third sector spaces for bringing people together to achieve shared interests.

The disappearance of meeting halls and the erasure of the social good that they bring poses the question: What is the fate of our collective future and democratic systems? As many town squares have moved to virtual locations my photographs aim to highlight this older model for social interaction. This resonates in this moment with a particular force as we look for safe, nonpartisan and secular environments to engender solidarity among citizens.

This multi-year and ongoing photographic exploration began in collaboration with my late husband, Andrew S. Flamm (1967-2018).

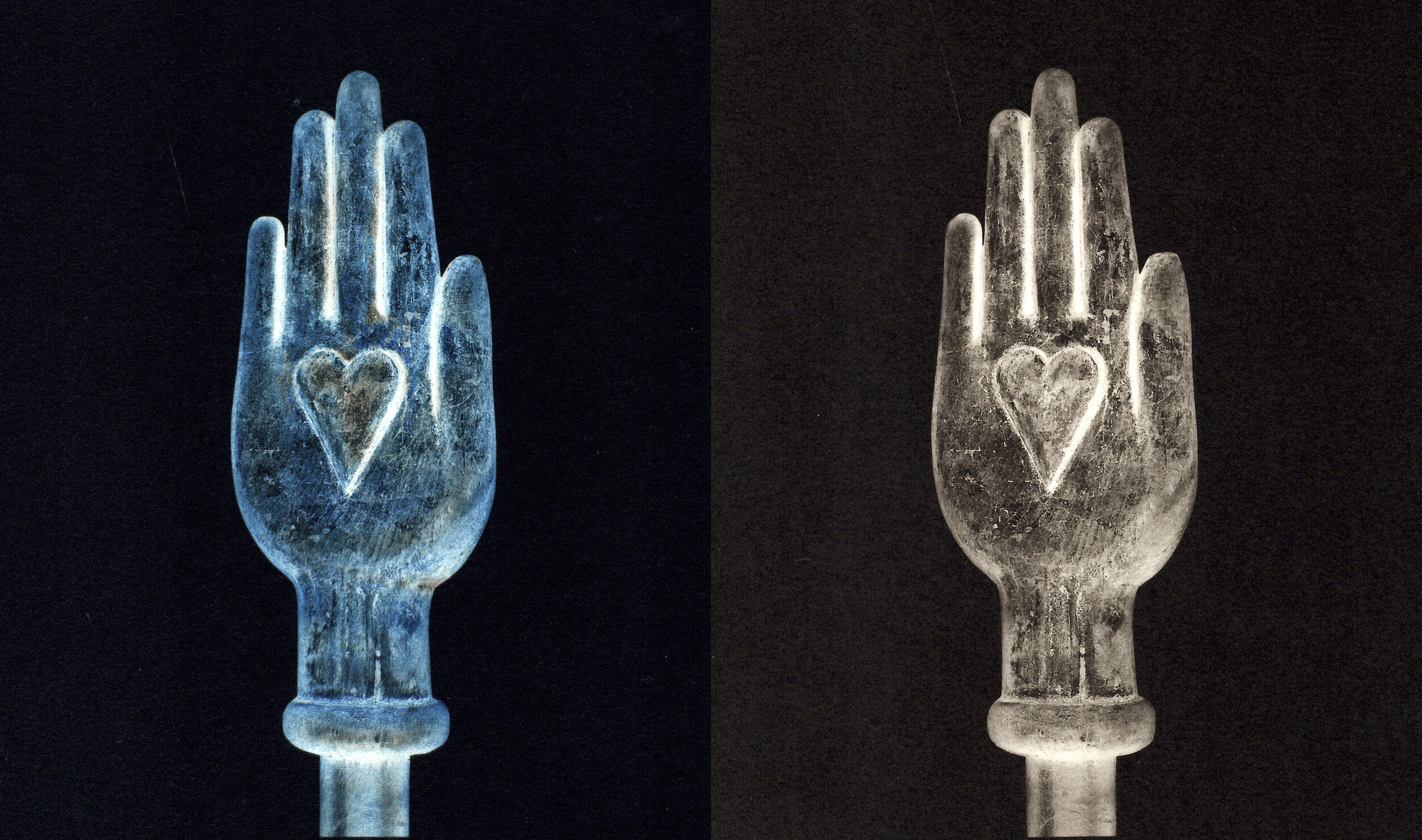

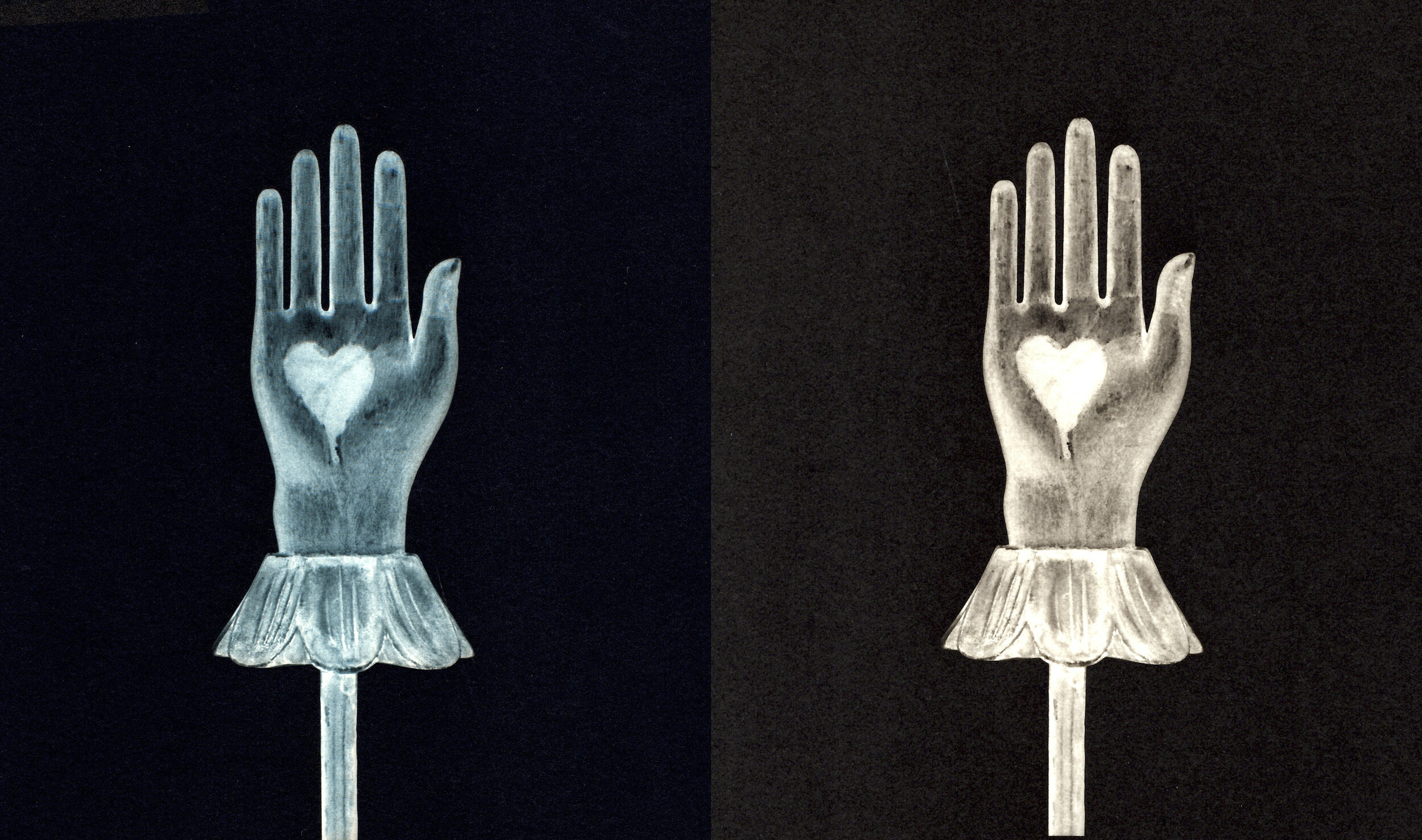

Material Culture

These prints are part of an evolving series that appropriates the material culture of American Fraternal Organizations as part of the boarder project: Meeting Hall Maine. For instance, heart and hand staffs are used by the Independent Order of Odd Fellows as teaching tools symbolizing, “That what ever the hand goes to do the heart must go with it”. The sun and the moon and “All Seeing Eye” frequently appear in fraternal imagery. The later represents the cyclical patterns found in nature. The eye represents an omnipresent power in the universe. The hammer striking the bell reflects that human life is finite.

Album Series

Like nature itself, the repetition and proliferation of photographic imagery is used in this series to echo the rhythms of the natural world. My painted imagery or a found photograph have become the point of origin for exploring the permutation of color, pattern and texture that can emanate from a single image using layered combinations of historic photographic printmaking methods. Sequenced together into nonlinear compositions the prints express the repetition yet endless variation of time.

“A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order”. ––– Jean-Luc Godard

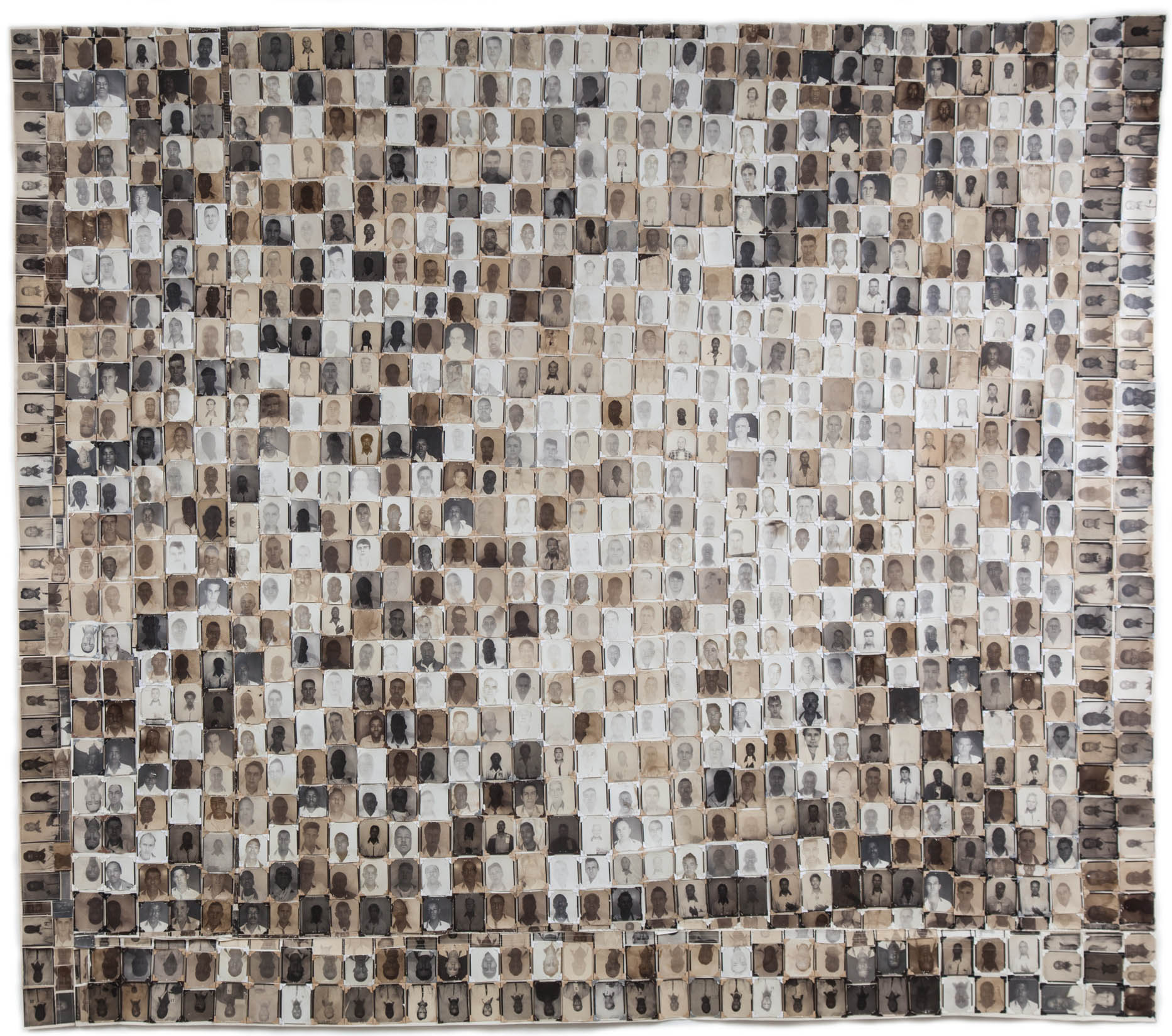

Found Photo "Quilts"

In this series each piece is formed around a collection: mug shots, school pictures or a common snapshot pose. Hundreds of found photos are composed together and sewn onto canvas. From a distance the repetition of shapes and tones read as an abstraction, and upon closer review offers the detailed truth of an individual’s existence. These photographic expressions typify how portraiture, in particular, has proliferated since the advent of photography and underscores its role in forming our cultural and personal identities.

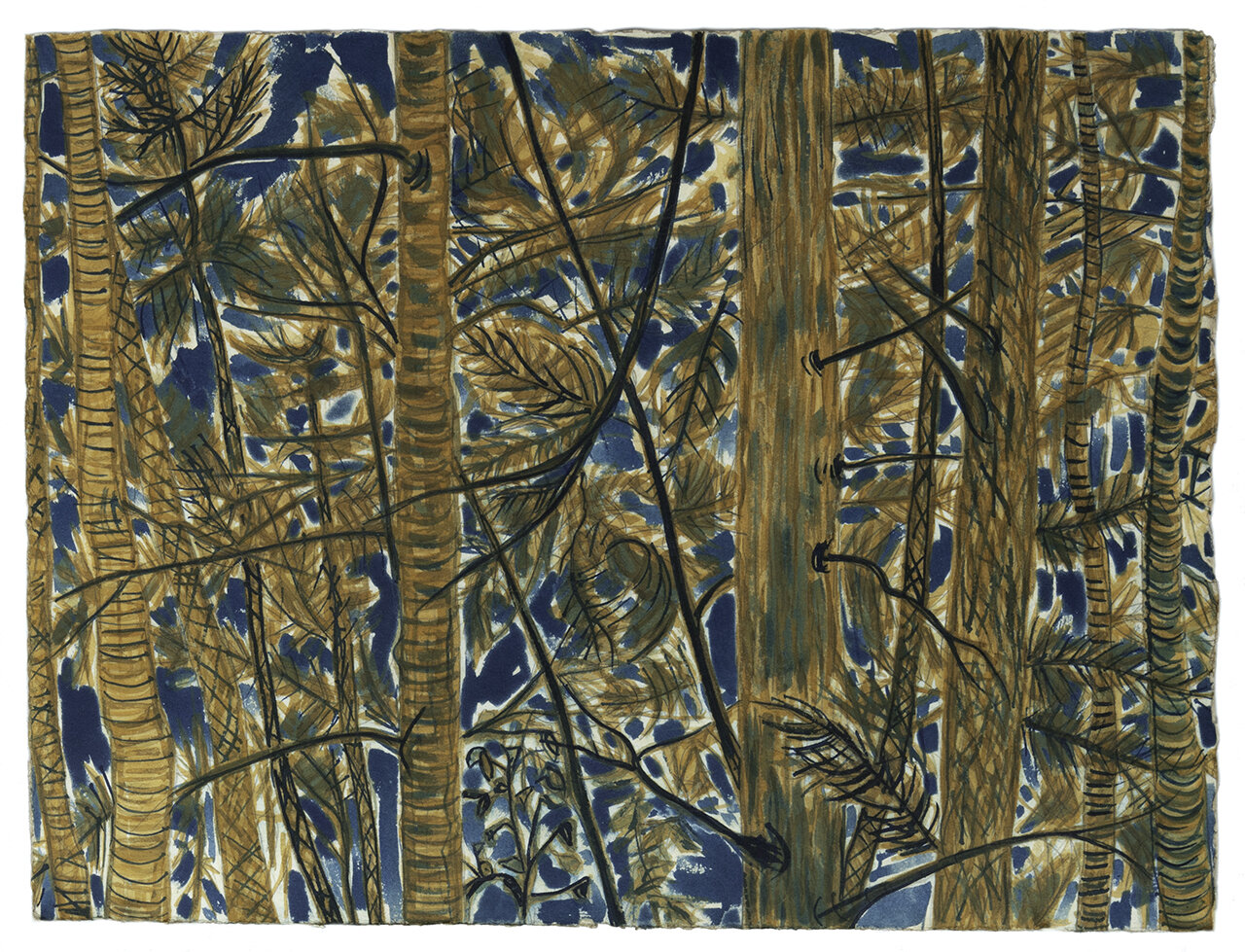

Camera-less Photographic Painting

My painting and photography practice inform one another bringing about hybrid works that reflect the historical dialogue and influence that has existed between these two mediums since the advent of photography.

In this series of camera-less photographic paintings, I use photochemistry in lieu of traditional paint mediums which forces me to be more primitive in my expression. My mark making is used in place of a negative or object as is the case in a traditional print or photogram. Unlike a Chemigram both light and chemistry are used to form my images. This work runs parallel to the groundswell of camera-less photographers working today and adds to the conversation of one-of-a-kind photographic imagery where all methods are in play.

.

Mug Shot Portraits

This ongoing series is painted from mug shots. Inspired, in part, by photographic mishaps, such as, the painterly quality of an over or underexposed print. I then turn a painted image back into a photograph (with the use of digital negatives and historic photographic processes) to further explore the confluence of painting and photography. In doing so, I capitalize on the ability to create print multiples of an image that are then over painted to make unique permutations.

Found Photos

As a student of Ray Yoshida’s at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I learned early on that the importance of authorship is secondary to the emotional value of an object and that discovery often begins with the mundane process of wading and sifting through vast amounts of our material culture. Vernacular objects and images have enriched my artistic practice by broadening my own ideas of approaching, making, seeing and defining art.